Text: Berit Norstedt

Photo: Staffan Norstedt

First published in Örnsköldsvik's Allehanda on September 28, 1973

The Chikankata mission station in southern Zambia is run by the International Salvation Army in collaboration with the Zambian government. There is a hospital and a leprosy colony with 250 patients each, and a secondary school with approximately 450 students. Nurses and laboratory assistants are also trained at the hospital.

MP3 file

Audio tape with interview by Berit Norstedt recorded in 1973:

Margaretha Erlandsson

Music from Chikankata

(Table of Contents)

The location is isolated. From the main Lusaka — Livingstone highway, you have to travel on a bad dirt road for three miles to get there. Mail and some supplies are picked up in Mazabuka, which is a few miles south on the main road. But most provisioning takes place in the capital Lusaka, about 15 kilometers from there. Telephones and electricity are available nowadays, but until just a few years ago all power came from a generator, which was only connected for a few hours a week.

Chikankata is very beautiful, in the middle of a fertile agricultural district on a high plateau. Villages of thatched huts climb the hillsides. Nearby there are large farms with white owners, but on experimental farms Zambians are also taught to run modern agriculture. The hospital consists of white single-storey buildings embedded in greenery. Both patients and visitors go in and out freely. Some light fires and cook their own food in the park. Sick people stand in the open windows of the isolation rooms and talk to people outside. Pregnant women resting under a tree. Leper, who has lost both fingers and toes, sits on a farm and weaves baskets. When necessary, they use their mouths to help.

In the hospital's entrance stands a bust of the Salvation Army's founder, William Booth, but everyday life at Chikankata has no particularly religious character. Many of the employees are not religious or belong to denominations other than the Salvation Army. But on Sundays, the whole area resounds with the Army's happy songs, which seem to fit well with the local musical tradition. In the large school church, the students from the secondary school gather for high mass together with the military officers, who are all dressed in white tropical uniform. A little later, a service is held with the lepers in another chapel. There the crowd is great and the congregation more varied, and afterwards they continue to play and sing outside. From the hospital, the patients can be heard from time to time singing arm songs in improvised choirs.

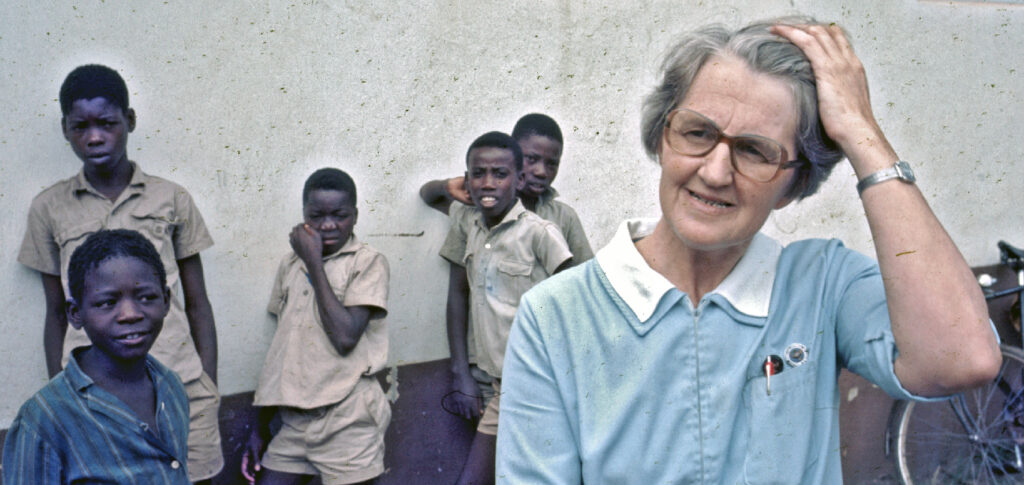

Ten nations are represented among the missionaries at Chikankata. One of them is the nurse and rescue officer Margareta Erlandsson from Trollhättan, who has worked there for eleven years. She talks about the hospital's everyday life:

- The day begins at a quarter past seven when we have morning prayer with the nursing students. After this they and the sisters go to their wards. There is already full activity there. We try to limit visits to the afternoons, but many patients are already visited early in the morning. There is a special house for the relatives to spend the night in. If they cannot afford other gifts, they give food to the sick, which is not always appropriate.

- In the children's ward, where I worked for ten years, the patients scream because their mothers have left them. But pretty soon they fall silent. Then you are busy washing children, giving them breakfast, making beds and cleaning as you usually do in a hospital. The children who can run out and play in the garden outside. Most people are satisfied with their existence here. The Zambian staff helps them sing children's songs from home. Sometimes they also sing choirs, which they have learned here at the Army.

At some of the beds in the children's ward, the mothers are sitting with their children. With little Victoria, both parents watch. She had undergone a lung operation the day before with only sedatives and local anaesthetic. She sat very still while a rib was removed. (Anesthesia does not occur at Chikankata. It is considered too risky, as you do not have access to special anesthesia staff.) Now she is in pain and crying and receives a nutritional drip.

- The parents may have first gone to a clinic with their sick child, but the treatment was not as successful as they expected, says Margareta Erlandsson. Then they tried the medicine man in the village, and then they went to the nearest hospital. It happens that they have gone to many hospitals, and when they come here to Chikankata, the child is so sick that we cannot save it. It dies.

- Sometimes the parents try to bring the children home early. They want to try the wizard doctor in the village. Here is e.g. a TB-sick teenage girl, who considers herself possessed by an evil spirit. Sometimes she has convulsions, and her vision becomes glassy. She and her parents live in the transition between an old and a new era, and they cannot accept the doctors' and nurses' view of the disease. The parents have just been sent home because they made the treatment difficult.

- Sometimes sick children come who look like inflated balloons. They have developed an abnormally large stomach from the one-sided cornmeal diet. In the villages it is the man's privilege to eat first. If there is anything left after the adults have eaten, the child has the right to this. When they enter the hospital malnourished, we teach them to eat eggs and meat and vegetables, which give them protein and vitamins. It may take several months for the body to return to nutritional balance. Then you first see that the edema disappears and the condition improves.

- When children come here for other illnesses, it often turns out that they also have TB. We keep a tubercle-free child for three to six months. Then we send him or her home to the village, if there is an opportunity to continue the treatment at a clinic. Ideally, we keep the child in the hospital for six months, and then there are not so many relapses.

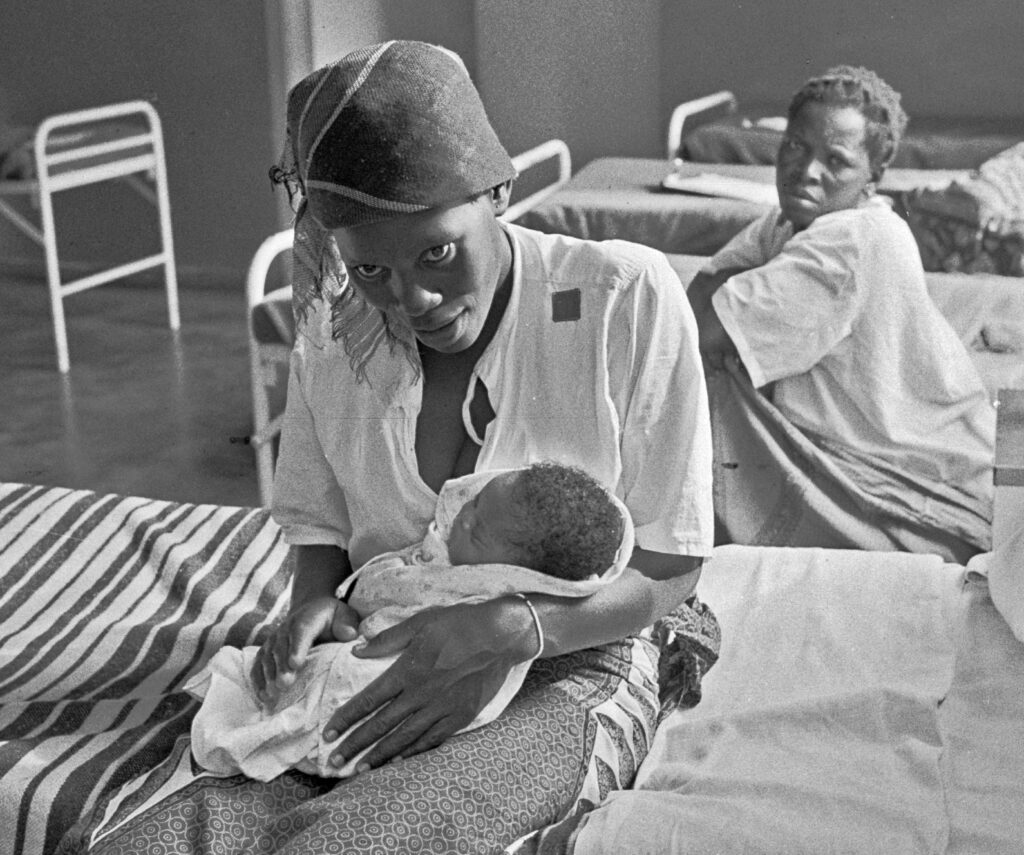

At Chikankata there is also a BB ward with 30 places, which is a gift from Svenska Rädda Barnen. It is becoming more and more common for people to give birth to their children there instead of at home in the huts. Since there is little communication from the villages, the expectant mothers arrive at the hospital well in advance of the birth and then live together in a special room.

The hospital has three simple incubators. During June-August it is cold indoors, and those born prematurely must be kept in even heat. While roaming-in has been introduced as a novelty in Swedish hospitals in recent times, it is a matter of course in Zambia. The children do have their own beds in their own room, but all day they lie in mother's bed, while she herself sits next to it. Fixed breastfeeding times are an unknown phenomenon. You feed your child when you want. Many Zambian women are comfortable with bottle feeding, but nurses and doctors are trying their best to encourage breast feeding. If the bottle is not kept perfectly clean (and that is impossible in the villages), the baby gets stomach ailments, which can lead to death. On Zambian graves, the dearest possessions of the deceased are usually placed. And there are pathetically many baby bottles on the children's graves.

Before mothers of multiple children leave the hospital, they are talked to about birth control. Taking birth control pills is considered too complicated. But if they have received permission from their husbands, an IUD is inserted.

While the Chikankata hospital used to mostly take in the already sick, it now also focuses on preventive treatment. You go out twice a week and have time to visit 13 different places every month. The children receive a triple vaccine and are vaccinated against TB, polio, measles and smallpox.

-Last year we had approximately 20,000 visits from children and 800 from mothers, says Margareta Erlandsson. Child mortality is still very high in Zambia, but if the preventive activities and checks continue for another ten years, we will probably see a decline.

Many of Chikankata's adult patients have TB. In the past, they stayed in the hospital for a year or two compared to two or three months now, if they received treatment in time. Then they go home and are given their tablets every fortnight by nurses and medical assistants at the clinics. Every three months, they must return to the hospital, to be X-rayed and see the doctor.

Leprosy is also, a very common disease in Zambia. At Chikankata, the most severely affected are cared for in the hospital's emergency department. Those who came under care in good time live in one of the three leprosy villages: one for men, one for women and one for families where both spouses have leprosy. The villages consist of small brick houses with tin roofs and communal hygiene areas. Cooking fires burn outside the houses, and there are corn fields and chickens. While medicine is used to prevent the disease, people live almost as if they were at home in the village.

In the past, leprosy was considered an incurable and unclean disease. Today, its progress can be stopped, but often nothing can be done about the damage that has already occurred. They try to operate on damaged parts, but sometimes amputation is the only way out. At Chikankata, a physiotherapist exercises the hands and feet of the sick. It is important that the muscles are kept active. They also have their own cobbler, and all leprosy patients are given shoes to protect their feet. The shoes must be soft and are therefore made of rubber tires. You must not risk e.g. nails go into the feet, because leprosy causes you to lose feeling in the affected part of the body.

The elderly with leprosy are generally not accepted in their villages, if they are sent home after treatment. Therefore, they must remain in the hospital. Men and women each have their own house, which consists of a single room with beds along the walls. They are far from the abodes of joy, but still provide shelter for the outcasts.

- Here at Chikankata we had the country's first nursing school, says Margareta Erlandsson, but now there are two more, in Lusaka and Kitwe. We train assistant nurses, and here they have greater responsibility than at home in Sweden. For a time we also had a higher education here, but now it only exists in Lusaka.

- These days it is common for girls to go to school as well. This results in a higher bride price. When it is decided that a girl should be educated, e.g. to nurse, it is an important step. If she doesn't do well and has to return to the village, she has lost all respect and is a total failure. If, on the other hand, she succeeds and gets a well-paid job — 100 kwacha (700 kroner) a month for a nurse, she can more or less support her entire village. She might send home 90 kwacha to the family and keep 10 for herself. In Zambia, becoming a nurse is popular. If asked why they want to become one, the girls usually say it's because they want to serve their country and their people. But in general there are probably financial motives behind it.

- Taking care of this teaching requires a lot of patience and great understanding, says Margareta Erlandsson. How should e.g. a girl know what good hygiene means, when she grew up in a hut with a dirt floor? Here at school, she must learn the cleanliness that a Swedish girl has learned in her parents' home. Then the girls are trained inside the hospital and get to put their knowledge into practice there. It is not easy for them and their teachers, but many become very good nurses, which we can recommend to different places in the country.

- Over the years, I have seen big changes here, says Margareta Erlandsson. Before, the villages were bigger, but now they break up into smaller villages or build their own houses and call them by their own names. As the people break out of the tribal system, they also gain greater national consciousness. They walk longer distances than before, and they travel to Mazabuka and Lusaka. Clothing has improved a lot, but if you go down to the Gwembedalen you will see that many people go naked. They still have a lot to learn about maintaining themselves. Hygiene needs to be improved, and the food must have a better composition. This transformation takes time.

- For my personal part, I often compare the conditions here with what I read in the history books at home about what it was like in the Nordic countries in the 19th century. The school was e.g. the rich man's privilege, and only in the 20th century did the school system reach the workers. Schools are being built here these days, but still many cannot go to school. There may not be a school in their district, and the roads are long and difficult. There are still boys and girls who walk many, many miles to get to school. They get to live there, and the next time they come to the village, six months or a year may have passed.

- But although many changes are taking place, traditions live on. The Tonga people, who live around here, have a matrilineal society. Dena, the oldest woman in the family, is very powerful. If the parents come here to the hospital with a child and it dies, they are not allowed to mourn it and bury it. They have to wait until the old woman comes and takes care of it. The teenage girls are kept locked up in a house in the village, to be taught cooking and other women's chores and to be initiated into the secrets of life by their grandmother or grandmother. In the past, this inauguration took six months, but now two weeks are enough. It is common for the schoolgirls to take the opportunity to do this when they have time off.

- You strongly feel the responsibility to help each other. One prepares e.g. the fields together. If one person gets 100 sacks of maize one year while someone else in his family gets a smaller harvest, the former shares in exchange for a promise of repayment the next year. When someone is allowed to study, it is a matter for the whole family. Those who helped financially, each with their small contribution, can then count on help when they get into difficulties or get old.

- Much of the old must be broken down. But in order to build something new, you have to have principles to follow, so that there is a good result, says Margareta Erlandsson.